Stadiums Aren’t Fated to Disrepair and Disuse – History Shows They Can Change with the City

Stadiums are among the oldest forms of urban architecture: from Olympia to Rome, stadiums were at the centre of the Western city, well before the great medieval cathedrals and the railway stations of the industrial revolution.

Today, however, stadiums are regarded with growing scepticism. Construction costs can soar above £1 billion, and stadiums finished for major events such as the Olympic Games or the FIFA World Cup have notably fallen into disuse and disrepair.

But this need not be the case. History shows that stadiums can drive urban development, and adapt to the culture of every age. Even today, architects and planners are finding new ways to adapt the monofunctional sports arenas which became emblematic of modernisation during the 20th century.

Adaptable amphitheatres

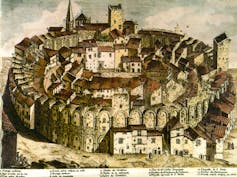

The amphitheatre of Arles, with a capacity of 25,000 spectators, is perhaps the best example of just how versatile stadiums can be. Built by the Romans in 90 AD, Arles amphitheatre became a fortress with four towers after the fifth century, and was then transformed into a village containing more than 200 houses. With the growing interest in conservation during the 19th century, the structure was converted back into an arena, for bull racing.

The imposing arena of Verona, with space for 30,000 spectators, was built 60 years before the Arles amphitheatre and 40 years before the Colosseum. It has endured the centuries and today is considered one of the sacred temples of opera, thanks to its outstanding acoustics.

Research by Taisuke Kuroda of Kanto Gaukin University has revealed the Piazza dell'Anfiteatro in Lucca (10,000 spectators) as another impressive example of an amphitheatre becoming absorbed into the fabric of the city.

The piazza evolved in a similar way to Arles, and was progressively filled with buildings from the Middle Ages until the 19th century, variously used as houses, a deposit of salt, a powder magazine and a prison. But rather than reverting to an arena, it became a market square, designed by Romanticist architect Lorenzo Nottolini. Today, the ruins of the amphitheatre remain embedded in the shops and residences surrounding the public square.

A place for the public

There are lots of similarities between modern stadiums and the ancient amphitheatres intended for games. But some of the flexibility of such arenas was lost at the beginning of the 20th century, as stadiums were developed using new materials such as steel and reinforced concrete, and made use of bright lights for night time matches.

Many modern stadiums are located in suburban areas, designed for sporting use only and surrounded by large concrete parking lots. These factors mean that they can be less accessible to the general public, require more energy to run and contribute to urban heat.

But architects such as Herzog & De Meuron, Zaha Hadid Architects and Toyo Ito see scope for the stadium to help improve the city. Among the current strategies, two seem to be having particular success: the stadium as an urban hub, and as a power plant.

There’s a growing trend for stadiums to be equipped with public spaces and services that serve a function beyond sport, such as hotels, retail outlets, conference centres, restaurants and bars, children’s playgrounds and green space. Creating mixed-use developments such as this reinforces compactness and multi-functionality, making more efficient use of land and helping to regenerate urban spaces.

This opens the space up to families and a wider cross section of the middle class, instead of catering only to sportspeople and supporters. There have been many examples of this in the UK: the mixed-use facilities at Wembley and the Old Trafford have become a blueprint for many other stadiums in the world. And the Fulham FC Riverside Stand Redevelopment – due to be completed in the next two years – will extend the riverside boardwalk, adding housing and retail.

Powering up

The phenomenon of stadiums as power stations has arisen from the idea that energy problems can be overcome by integrating interconnected buildings by means of a smart grid, which is an electricity supply network that uses digital communications technology to detect and react to local changes in usage, without significant energy losses. Stadiums are ideal for these purposes, because their canopies have a large surface area for the installation of photovoltaic panels, and rise high enough (more than 40 metres) to make use of micro wind turbines.

Freiburg Mage Solar Stadium is the first of a new generation of stadiums as power generators, which also includes the Amsterdam Arena and the Taiwanese Kaohsiung National Stadium.

Kaohsiung National Stadium, inaugurated in 2009, has 8,844 photovoltaic panels producing up 1.14GWh of electricity annually. This reduces the annual output of carbon dioxide by 660 tons and supplies up to 80% of the surrounding area when not in use. This is proof that a stadium can serve its city, and have a decidedly positive impact in terms of reduction of CO₂ emissions.

Stadiums remain the immortal engine of the city. In every era, the stadium seemed to have completed its scope, but instead it has acquired new value and uses: from military garrison to residential village, public space to theatre and most recently a field for experimentation in advanced engineering. Now, rather than becoming something else, the stadium brings together multiple functions, to help cities create a sustainable future.

Alessandro Melis, Principal Lecturer in Sustainable Cities, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

cover photo © unsplash